I've spent most of my life in love with history. As a little boy I played with toy soldiers in some sort of American Revolutionary kit. My parents bought me those hardback American Heritage volumes on great events like the Revolution and the Civil War, which I couldn't put down. My grandparents and all of my older relatives—all Eastern European immigrants—filled my head with stories from their childhoods, long ago and far away. As a teenager I'd go with my father—a university professor—to his office on weekends and head for the university library's dungeon, where they kept the bound volumes of the New York Times, and pore through old issues from World War II, or whatever interested me that day.

I'm not sure exactly what I loved about history. Maybe the sheer craziness and improbability of some or a even a lot of it: a teacher in college discussing modern European history used to say, "If you didn't know it was true you'd think it was fiction," a sentiment that most of us feel about contemporary American public affairs, I think it's fair to say.

Or perhaps it was the romance of time and consciousness travelling to far away places and times, the sheer exotica of it all. I'm not a particularly visual person, so it's not as if I easily conjured up what Tsarist Russia looked like, or even felt like, when my grandfather told me stories about experiencing electric lights for the first time in a town dozens of kilometres from his own home.

As my own small intimate family world became more complicated, sadder and harder, any amateur practitioner of psycho-babble could tell me that perhaps I sought to escape my troubles by running away in my mind to some other time and place, that I replaced the people I lost with new connections found in the lives of others. History is a story about the past and perhaps I just plain liked it more than my own life story.

Whatever the reason my sheer love of the past, of both my ability to connect to it yet feel separate and therefore intrigued by its otherness, never left me. Lots of schooling added layers to that personal feeling, now I know lots of fancy ways of "interrogating" the past, asking analytical questions, thinking about problems, blah blah blah. Those methods for me add to never detract from my deeper love of the subject.

So it's with a lot of sadness that I hear the oft-sounded complaints from others that history bores them. Too factual, not enough compelling story. Or too narrative and not intellectually disciplined enough. Too intellectually dispassionate and not personal enough. Or too far away, too hard to feel a connection to something so literally strange.

I hear all that. It helps most of us to connect the micro and the macro, the personal and the social, and then gradually learn how to toggle back and forth between them. When I taught 10th grade European history—a subject which I knew well but for which pedagogically speaking I was completely in over my head—I assigned a family history project. One student, a lovely well behaved but not particularly self confident person at the time, worked on her family's story from Vilna prior to the Holocaust. For an artifact she utilized a picture of her Vilna relatives, including her grandfather as a boy/young adult, on a family business truck. For the next three years we would talk about "The man on the truck": shorthand for the huge events of the rise and fall of Jewish life in Europe, modern social and economic trends like class and capitalism, migration, as well as the Holocaust and World War II. All somehow embodied in "the man on the truck."

So the other day I had my own "man on the truck" episode. I participate in a book group that emerged out of the Tzion program I founded that teaches the history and ideas of Zionism and Israel. The group met on Sunday and at the end of the evening decided for next time to read Vladimir Jabotinsky's novel, The Five. It's a somewhat autobiographical novel, set in Jabotinsky's hometown, Odessa, at the turn of the twentieth century.

I sent the link for the book to the group, an email cohort which somehow includes my uncle, who God willing turns ninety-nine this June. He wrote this response to me:

"Dear David, Jabotinsky used to be a subject of dinner table conversation with Uncle Aaron. You remember that he and Aunt Fan were members of the Odessa young intellectual group who were involved in the 1905 revolt."

My uncle's uncle, Aaron Moldaw, left the Ukraine and arrived in Boston in 1906, and then brought the rest of his family, including my grandmother, his sister, to America in the years before and after World War I. I knew he'd left Russia because of activities relating to the failed revolution of 1905. But I never knew the Jabotinsky connection. All of these years I've been reading and teaching the great man and his life and times, and I never knew that I'm separated by him only by two degrees.

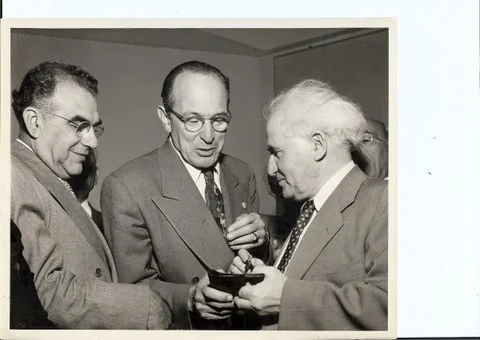

I have a picture of my Great Uncle Aaron with David Ben Gurion and wonder now if he told DBG about his connection to the Revisionist leader, knowing the antipathy that existed between them. I'll probably never know the answer to that. I also have a condolence letter that Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik wrote to my Aunt Fan when my uncle died, yet another connection to a an important figure in modern Jewish life. So I now feel even closer to the story of my family, to my people, and to the story of Zionism and Israel. Who knew? I wish all students will experience that. They may if they keep reading and trying to discover history for themselves. Consider such discovery your own personal historical version of the search for the missing piece, the seder's notion of the Afikoman. Enjoy the hunt.

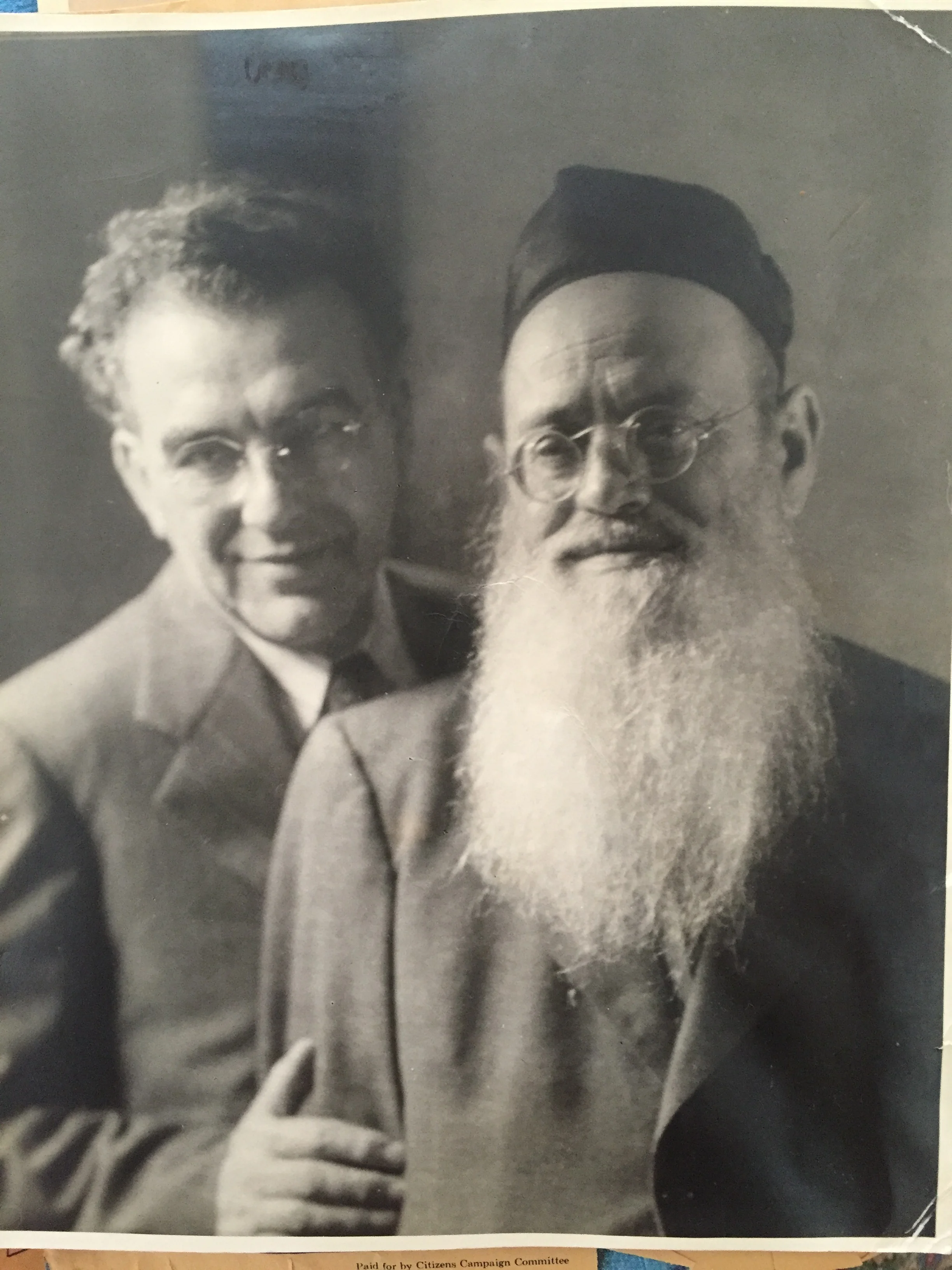

Fan and Aaron Moldaw